[T]he more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel. [Warhol, ca. 1975]

The advent of theoretical approaches to art that occurred in the twentieth century has produced wide-ranging and significant impacts in the art world. The destruction of logo centric metanarratives in the years leading up to and following the Great War produced a variety of perspectives through which society, the individual, and the worlds of art and politics could be understood. Two of the most potent and influential worldviews to emerge from the rubble of Europe were the schools of Marxism and Psychoanalysis. Both addressed and presented newfound anxieties and threats to the established world - godless realities in which dominance, alienation, repression and insurrection were integral to our reality. In the world of art, this led to a reappraisal of pre-existing artworks through the prisms of socioeconomics and psychoanalytic analysis, and all future artworks were to be subjected to a myriad of conflicting and complimentary perspectives in an attempt to decipher the new reality of a new world. In simple terms, we use theories to explain and organize the world we live in. When theories are explained briefly, a necessary reduction of their complexity and richness occurs. Acknowledging this limitation, I have chosen Marxism and Psychoanalysis as two approaches to engage with a particular work of art.

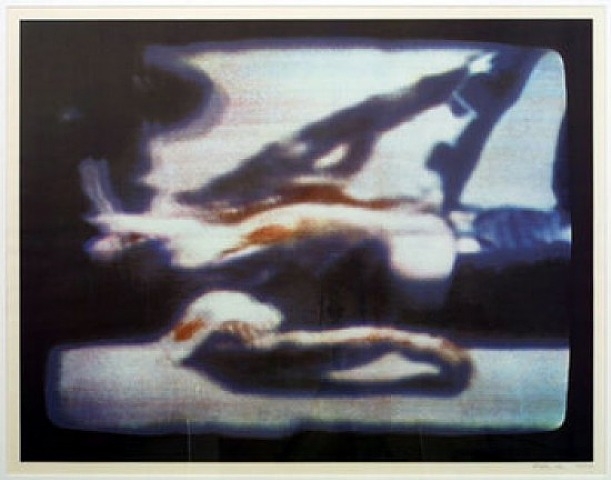

In the art world, no artist embodied the fractured, elusive, and enigmatic nature of the twentieth century better than Andy Warhol. I have chosen to interpret Warhol through the aforementioned approaches, specifically looking at one painting, Green Burning Car, from his ‘Death and Disaster’ series of 1962-1964. This offers a social-political commentary upon the dark side of American life in the nineteen-sixties, documenting suicides, car crashes, race riots, electric chairs and atomic bombs. From a Marxist standpoint, Warhol’s preoccupation with the process of production in an artwork, and the way in which he changed the way mass audiences consumed art, was his greatest contribution to modern art, and ensures his legacy. He claimed that he only painted what he loved: money, celebrity, and consumerism - all of which were emblematic of the hyper-industrialised reality of post-war mass democracy. I argue that the serious subject matter of the Green Burning Car silkscreen, and all the pieces within that series, covertly critique the situation that Capitalism has left society in, and address the feelings of alienation fostered by the consumerist American dream to which the the Western world had, by then, largely been programmed to aspire.

Marxism as a movement offers a critique of Capitalist society and presents a materialist understanding of history. It prioritises the struggle of the social classes who, it holds, need to overcome their disenfranchisement through revolution in order to gain political power. It is a movement which found its inception in the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Theories have since been built upon these texts which have lead to diversification within Marxist thought and practice. And so, with respect to Warhol’s work, and knowledge of the oppositional and dynamic positions within Marxist theory across many disciplines, I want to narrow the focus of this discussion to Marx’s theory of alienation. I hold that while on the surface Warhol represented Capitalism in its purest, most unadulterated and idolised forms, at a deeper level he was critiquing the technology and mass consumption which served (and, indeed, serves) to numb and reduce the populace into a state of ordinariness and alienation. Marx believed an experience of alienation was caused directly by Capitalism. In the capitalist labour process one does not identify with the product of one’s own labour - this product becomes a distinct, independent entity. Through the process of labour, a person sells themselves as a commodity, and, when reduced to a commodity, the identity of the self is lost. Thus man, now feeling useless, engages in a futile attempt to end his sense of loss and alienation through escalated material consumption. A person begins to identify themselves through their commodities; they find their character in their car, ipod, kitchen and DIY equipment. Thus, ‘all objects for him become the objectification of himself... and objects [for him will] confirm and realise his individuality once they become his objects’ (Marx, 1844, p.25) This process develops through the mechanisation of industrial production and the division of labour. Marx states ‘We have before us the objectified essential powers of man in the form of sensuous, alien, useful objects, in the form of estrangement, displayed in ordinary material industry.’ (Marx, 1844, p.27) As a consequence of this conditioning, we have been morally alienated by the practice of modernity. We have become predictable, mindless robots, manipulated to the extent that commodities have taken on cultural associations, slave to the simultaneous generation and consumption of unending commodities.

The prevailing themes of Warhol’s work always originated in mass produced ideas and products. He took existing representations of reality and repackaged them for consumption over and over again, redefining the meaning of the artefact already existing and imbuing it with new significance when transported into a new context. When we look at the silkscreen painting Green Burning Car we see the same image produced multiple times on the one canvas. This repetition echoes the repetition of images on television and newspapers. It becomes a commentary on mass communications as well as mass productions. It is worth noting here the writings of mid-twentieth century retail analyst Victor Lebow. In an article entitled Price Competition in 1955 he acknowledged the consciously applied pressure that is essential in order to maintain high levels of mass consumption. According to Lebow, the most powerful way to control desires was through the use of media. He paid particularly close attention to television, which he said ‘achieves […] results to an extent no other advertising medium has ever approached. It creates a captive audience [and] submits that audience to the most intensive indoctrination.’ (Lebow, 1955, p.5)

Warhol’s decision to replicate the same image again and again is a fitting reflection of this relentless baraging of the mind by repetitive imagery. While his most famous works present multiple representations of celebrity icons and household goods, here his choice of image leads us to a more sobering, morbid place. In an interview with Gene Swenson Warhol recounted, ‘When you see a gruesome picture over and over again it really doesn’t have an effect.’ (Art News, 1963) What we see in Green Burning Car is the ultimate gesture towards Capitalist alienation, one which addresses commoditisation on two levels: first, we see the commodification of death purported by the media in its need to sell papers and generate publicity - the majority of the images in this series were taken from newspaper stories. Secondly, we encounter the apparently cynical and pessimistic appropriation of death by the artist himself in the production and sale of his work. It is significant here that the scenes of carnage and human obliteration are the direct result of man’s recklessness with a car, the ultimate status symbol of the postwar, capitalist, suburban utopia. With the traditional symbolic role of cars transgressed and subverted, Warhol’s images “represent a breach of faith in the products of the Industrial Revolution by featuring consumer products that bring death’. (Warhol, 1988, p. 16)

Capitalist alienation is perhaps most chillingly embodied here by the figure in the background that does not even turn to view the smoking car wreck, creating the impression that the carnage is as mundane and ever-present as to not warrant a cursory glance. Through the consistent sensory bombardment of mass media, and the image-saturated reality propagated by Capitalism, all the qualities considered as being essentially human (compassion, empathy, altruism) are submerged by the reduction of all phenomena to the status of disposable entertainment. Warhol acts here as an oracle of the current era in which the videotaped execution of dictators is robbed of all historical significance and reduced to the level of mere fodder for the consumer’s insatiable appetite for momentary distraction. The car crash victims themselves are nameless, dehumanised objects of a horror spectacle. They epitomise the common American man, the faceless, unknown everyman; they are ‘social unknowns, suffering what has been called plebeian catastrophes.’(Warhol, 1988, p16,) They embody the common man, broken and spent in the turning gears of a system that promises an American Dream and delivers a monolithic nightmare.

Marxist theory, as we have seen, interprets social reality through the modes of production and distribution, and the corresponding authoritarian constructs that characterise the capitalist social order. Psychoanalytic theory, on the other hand, focuses on the psychic life of individuals, not masses as a whole. By investigating the particular neuroses, sexual preferences, repressions and desires of the individual artist, the psychoanalytic theorist aims to explain the creative processes that led to the finished work. At this juncture I will be referencing the work of Freud, particularly focusing on the development of the drives. A drive, for Freud, is the biological demand on the cerebral life. The mind arises from the drive (Ego from Id). A drive has a foundation (bodily needs), an internal endeavour (temporary removal of the bodily needs), an external endeavour (steps taken to reach the final goal of the internal aim), and an object. We never experience the drive itself, just its demonstration or idea in the mind. In general the drives are linked to sexual instincts. From a psychoanalytic perspective, Green Burning Car displays some of the elements involved in Freud’s theory regarding drives, especially the death drives that are imbedded in our consciousness. For a number of years in the sixties Warhol was preoccupied with death and representations of death. It is generally acknowledged that he was fearful of his own bodily demise as well as the concept of death; he is quoted as saying ‘I don’t believe in it, because you’re not around to know that it has happened. I can’t say anything about it because I am not prepared for it.’ (Warhol, 1988, p.123) One can assert that this wilful evasion of the prospect of his own death manifested itself in the obsessive repetition and revisiting of macabre imagery in his work.

Freud attempted to ascertain why people are drawn to repeating traumatic events. He was particulary interested in why such a compulsion to repeat these events exists, as it appears to run contrary to what he asserts as our base instinct - the seeking of pleasure. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Freud, 1920), the egoistic and libidinal drives that characterise much of Freud’s work are supplanted by life and death drives. Freud analysed the post-traumatic dreams of soldiers, in which they seemed irrevocably drawn to reliving the most horrifying experiences of their lives in a way that suggested a masochistic refusal to abandon the painful past to simple memory. Freud came upon the idea of ‘compulsive repetition’ while watching his grandson play a game called fort/da in which he would compulsively throw his toys away and then retrieve them, in a game of disappearance and reappearance. The child seemed satisfied by causing the toys to be ‘gone’, relishing their subsequent return. This action was ‘repeated untiringly’ (Freud, 1920, p.599). This enactment of a distressing experience as a game was counterintuitive to the pleasure principle and pre-existing ideas of play. Freud seemed to think that this disappearance of the toy was in fact the child’s way of controlling the feeling of loss when the mother departed for periods of time. ‘Her departure had to be enacted as a necessary preliminary to her return, and that it was in [this] lay the true purpose of the game’ (Freud,1920, p.600). By actively reproducing the action of disappearance, the child locates a pleasure that makes it possible to tolerate the absence of the mother. Freud concluded that, running counter to our desire for pleasure was a symbiotic and seemingly counterintuitive impulse towards loss and pain. He posited that, ultimately, we are driven by a fundamental urge towards that which ends all suffering – death. It is “an urge inherent in organic life to restore an earlier state of things”, and as the inorganic precedes the organic, “the aim of all life is death.” (Freud, 1920, pp.612-613) Freud outlines that the death instinct is so deeply intertwined with the will to live that they cannot be separated:

the repressed instinct never ceases to strive for complete satisfaction, which would consist in the repetition of a primary experience of satisfaction...the backward path that leads to complete satisfaction is as a rule obstructed by the resistances which maintain the repressions (Freud, 1920, p.616)

These resistances are those of societal norms and values, the concept that you should love thy neighbour if you want to be part of a family and social life. Freud believes that the concept of loving thy neighbour is counterintuitive to our instinctual processes. This is how civilised society is controlled and as a result of this, a latent anger resides buried in the consciousness either projected inward or outwards towards the world. Impulses that lay in the ‘Id’ (that part of a personality which contains our primitive impulses such as sex, anger, and hunger) are not appropriate in civilized society, so society works to modify the pleasure principle. In Freud’s view, self-destructive behaviour is an expression of the energy created by the death instincts. When this energy is directed outward onto others, it is expressed as aggression and violence. He concluded that people hold an unconscious desire to die, but that this wish is largely tempered by the life instincts.

In an overt display of compulsive repetition, Warhol consistently returned to endlessly repeating images of death and destruction.Warhol’s preoccupation with death, especially violent deaths where people had taken risks (and deviated from the socially imposed norms Freud saw as the suppression of our natural desires and instincts) by jumping from high rise buildings, committing crimes that lead to capital punishment and, in the case of Green Car Burning, a man suspected of a hit and run accident, being pursued at high speed by police contain a menacing undertone. This man, impaled on a pole serves as a warning to all those who attempt to subvert societal norms through deviant behaviour. The images appearance in a newspaper is intentional on behalf of those who mean to maintain order. In Warhol’s case however, it is not the message of the photograph that intrigues him. For Warhol this preoccupation or obsession involved detachment and distance, as the subject escalated in intensity so the style of the piece became increasingly transparent. If we are to believe in the drive for death then it is Warhol’s unconsciously repressed drive that is propelling him forward into repetitively pursuing traumatic imagery and thoughts of death, despite his obvious fear and wish to stay alive. As a way of coping with his fears, much like the child, he tries to gain control of this trauma by taking the horror of death and desensitizing its presence. He mediates the image by his choice of dull green, avoiding primary colours, which strengthen the distance between himself, the viewer, and the image presented. This distance is also maintained in relation to the medium with which the image was captured, remaining twice removed by the neutrality of the camera shot and through its reproduction in the newspaper. Warhol can then respond to the image of death and not death in itself. In reproducing the image he mimics and diminishes the horror and impact of death, until ‘[...] the meaning goes away, [and you feel] better and emptier.’ [Warhol, ca 1963]

In an overt display of compulsive repetition, Warhol consistently returned to endlessly repeating images of death and destruction.Warhol’s preoccupation with death, especially violent deaths where people had taken risks (and deviated from the socially imposed norms Freud saw as the suppression of our natural desires and instincts) by jumping from high rise buildings, committing crimes that lead to capital punishment and, in the case of Green Car Burning, a man suspected of a hit and run accident, being pursued at high speed by police contain a menacing undertone. This man, impaled on a pole serves as a warning to all those who attempt to subvert societal norms through deviant behaviour. The images appearance in a newspaper is intentional on behalf of those who mean to maintain order. In Warhol’s case however, it is not the message of the photograph that intrigues him. For Warhol this preoccupation or obsession involved detachment and distance, as the subject escalated in intensity so the style of the piece became increasingly transparent. If we are to believe in the drive for death then it is Warhol’s unconsciously repressed drive that is propelling him forward into repetitively pursuing traumatic imagery and thoughts of death, despite his obvious fear and wish to stay alive. As a way of coping with his fears, much like the child, he tries to gain control of this trauma by taking the horror of death and desensitizing its presence. He mediates the image by his choice of dull green, avoiding primary colours, which strengthen the distance between himself, the viewer, and the image presented. This distance is also maintained in relation to the medium with which the image was captured, remaining twice removed by the neutrality of the camera shot and through its reproduction in the newspaper. Warhol can then respond to the image of death and not death in itself. In reproducing the image he mimics and diminishes the horror and impact of death, until ‘[...] the meaning goes away, [and you feel] better and emptier.’ [Warhol, ca 1963]

The repetition that characterises so much of Warhol’s work can be interpreted in different ways according to Marxism and psychoanalysis. My Marxist reading presents this as being symbolic of the bourgeoisie’s mass sedation via image saturation, something which robs the individual of agency, empathy, and, ultimately, social mobility. My psychoanalytic view presents this as the individual artist’s attempt to sublimate his anxieties about death in a child-like game of repetition, leading to a comforting numbness. Both theoretical approaches draw conclusions that, while superficially quite similar, are drawn from widely differing interpretive approaches. Marxism, with its materialist approach to reality, views the car as an agent of social mobility, a symbol of consumerist vanity, and a vehicle of man’s ultimate destruction. Psychoanalysis views the charred wreck of the car as the ultimate manifestation of the Id’s powerful death drive, an emblem of the destructive impulse latent in all humanity. One of the most important points to note is that while such readings offer fruitful insights into an artist’s work, limiting interpretations to one specific theoretical approach creates a danger of ignoring other active components imbued in the artist’s production. Psychoanalysis as a discipline has come under fire for its origins in the social mores of patriarchal nineteenth century Vienna, to the exclusion of Marxist, feminist, and other perspectives. I would further point out that a distinct reading in one approach is not always possible, as differing theoretical approaches often overlap, as one is often drawn from or influenced by another. In this case there are elements of Marxist theory which overlap with ideas based in Psychoanalytic theory. The psychological state (Psychoanalysis) of an individual is inherent in how the minority - according to Marx, the bourgeoisie - maintain and exert control over the masses (Marxism), and equally informs the instinctual drives (Psychoanalysis) which inhabit both our conscious and unconscious selves, which in turn determines the way in which we govern society (Marx). This merging of the principals of Marxism and Psychoanalysis in an attempt to interpret the world can be exemplified in a quote from Warhol himself;

‘I never think that people die. They just go to department stores.’ [No date]

Bibliography

Bibliography

· Bersani, L., (1986). The Freudian Body: Art and Psychoanalysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

· Freud, S., (1991). Civilisation, Society and Religion. London: Penguin Books

· Freud, S., (1920). ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’, in Gray, P, (ed.) the Freud reader. New York: Vintage, pp594-626.

· Freud, S., (1923). ‘The Ego and the Id’, in Gray, P., (ed.) the Freud reader. New York: Vintage, pp 628-658.

· Laing, D., (1978). The Marxist theory of Art: An Introductory Survey. Colorado: Westview Press

· Lebow, V., (1955). ‘Price Competition in 1955’ Journal of Retailing Spring Vol. 31 no. 1, pp 3-9

· Marx, K., (1844) ‘Production and Consumption’, in Lang, B. AND Williams, F. (eds.) Marxism and Art. New York: David McKay Company Inc, pp31-39.

· Marx, K., (1844) ‘Property and Alienation’, in Lang, B. AND Williams, F. (eds.) Marxism and Art, New York: David McKay Company Inc, pp21-31.

· Swenson, G., (1963). Andy Warhol, Art News. Available at http://www.mariabuszek.com/kcai/PoMoSeminar/Readings/WarholIntrvu.pdf (accessed 6 January 2012)

· Walker, J., (1994) Art in the Age of Mass Media. (2ed) London: Pluto Press.

· Warhol, A., (1975). The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (from A to B and back again). New York: Harcourt Brace.

Warhol, A., (1988) Death and Disasters. Houston: Houston Fine Art Press.